The first time I taught interpersonal communication was in September 1994. Back then, when I told my family and friends what I taught, they would try to hide their smirks and say, a little mystified, “There are actual college classes about that? Don’t you learn how to do that just by being alive?” I don’t really hear that anymore. Today, people get it.

Interpersonal communication is the social scientific study of how we talk to one another in gatherings too small to be called public speaking. The most basic unit of all is what we call a dyad, just two people in conversation. But interpersonal communication only makes sense against the backdrop of the kind of relationship the communicators have: friends, co-workers, family members, spouses, teacher and student, detective and suspect, the possibilities are endless.

As the worst of the anti-Covid measures were lifted on campus and we could meet again in person, I was so very thankful for what I think we’re often guilty of taking for granted: being together is a glorious blessing that we only appraise rightly after we’ve been kept apart. Togetherness is magic. In Genesis, before the fall, before sin entered the world, the very first thing God said was not good was that Adam was alone. We were not created to be alone. God engineered us to thrive when we are together.

Interpersonal communication done well, then, is one of the best ways to foster togetherness, and I love that part of my job. But that does pose a reasonable question: if togetherness is so important to me, what possible sense does it make that I’ve decided to cross the planet’s largest ocean, set up shop in what might be the most different culture on Earth from my own, and stay there for an entire school year?

The truth is, God put Japan on my heart over twenty years ago, before my current students were even born. Then, Japan kept inserting itself into my story.

While coaching debate at the University of Georgia I hosted a team of college debaters from Japan. We threw a reception to welcome them, and someone made sushi. Now, I had never tried sushi before; in late 1980s Waco, they would’ve called it bait. But my very good friend who was my fellow assistant coach picked up a piece and said “Eat this and don’t ask me what it is.” I said “Yes ma’am,” and did what I was told. It was incredible. It was one the best things I’d ever tasted. I said “What is that?” She said, “Eel,” and I learned an important lesson about suspending judgment. The idea of eating eel would have killed my appetite, but when I first tasted it and then found out what it was, I loved it.

Soon I found myself living in Nacogdoches, Texas, trying to find something engrossing to fill my spare time. The pineywoods of east Texas are beautiful, and the people are warm and loving, but it is possible for a young man still in his twenties to find the town a bit dull, so I started learning to speak Japanese. Chiefly I did it to amuse myself, but occasionally I would throw in a Japanese phrase during a lecture to illustrate a point about cultural difference. Those examples came in handy, because as more and more classes were added to my assignment, I noticed that nearly all of them had a chapter on cultural difference: interpersonal communication, nonverbal communication, conflict management, all were incomplete without some attention to the cultural influence.

I began to dream about what God might have in store for me, as Japan continued to weigh on my heart. The opportunity to visit Japan came and went, unfulfilled, several times. I applied for a teaching job there yet, though I made the final round, was not selected. Upon learning how unreached Japan is by the gospel (a mere one half of one percent of the population of Japan is actively pursuing a maturing Christian faith), I planned a short-term summer mission trip that never materialized.

Along the way, I landed a professorship at Bushnell University and began teaching intercultural communication. For a lot of the major concepts in the class, the difference between the United States and Japan was the best possible illustration: individualism vs. collectivism, direct vs. indirect, emotional vs. reserved, high vs. low power distance. It became a running joke with my students: I could say “I just said ‘culture,’ so what is my example about to be?” and they would all respond, in unison, “Japan!”

Japan continued to draw me in. In May of 2021, I made up my mind to apply for Fulbright 12091-JA, Study of the United States, Teaching in Social Sciences and Humanities in Japan. But just like a grad student searching for a thesis topic, I had to dream up the proposal that I would ask the Fulbright body to support. I spent several weeks sifting through research reports and editorials about Japan, searching for anything that would merge my teaching specialties of debate and interpersonal communication.

That research clarified two things: First, Japanese teachers had spent decades trying to design a successful approach to teach English to their students. They had taken strides forward, moving from rote memorization to conversation practice, but they were at a standstill on one fairly specific problem: Japanese graduates sent out to interact with English-speaking colleagues from neighboring countries had little confidence in any work that required assertiveness. They struggled to negotiate and didn’t know how to play hardball. Their culture emphasized harmony and kindness, so elders taught juniors that speaking directly and forcefully was the same as starting a fight.

Second, Japan had a problem with loneliness. Since 2008 – coincidentally, the year after I arrived in Eugene – Japan’s population had been falling. Probably the biggest root of this trend was that a lot fewer young adults were marrying. In fact, a report released this year by the Japanese government indicated that about a quarter of adults in their thirties had no intention of getting married, and that the number of marriages in 2021 was the smallest since records had been kept.

Additionally, the phenomenon of 引きこもり(pronounced hikikomori), or social withdrawal, was ubiquitous. It describes a situation where someone will simply take to their home, sometimes even to their bedroom, and withdraw completely from interacting with the outside world. Roughly 1.5% of the population, more than one million people, are caught in this pattern. In February of 2021, the Japanese government created a cabinet-level Ministry of Loneliness to try to diagnose the problem and reverse it.

Once I had a grasp of these two issues, I had my project. I am a professor of interpersonal communication with roots in competitive debate, and I specialize in teaching how proper assertiveness that sticks to the issues can actually strengthen relationships instead of endangering them. I also give a lot of emphasis in my teaching to the power of listening to overcome loneliness by helping people feel connected and build trust. I proposed to teach about argument to help Japanese students get the most out of their English lessons, and to teach broader interpersonal communication skills to help them feel confident navigating difficult patches in their relationships as a protective factor against withdrawing and becoming hikikomori.

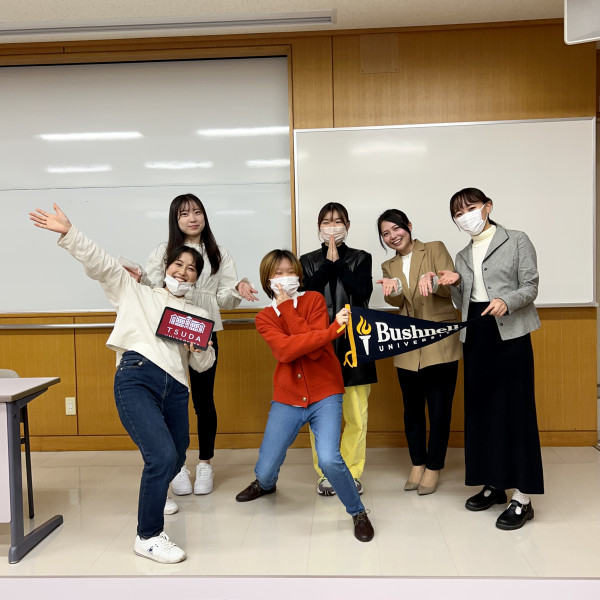

Tsuda University, which is a women’s college in the west end of Tokyo, is hosting me, and I will be teaching three classes for them. I will teach their undergraduate students classes in argumentation and conflict management, and then I will teach a graduate seminar in relational communication that explores the social science of how Americans start their relationships, maintain them, and repair them after hurtful events. I will also be teaching two classes at Tokyo University of Foreign Studies: nonverbal communication, and a special topics class about how story and storytelling shows up in just about every type of interpersonal encounter. Then, starting in February, I’ll teach two additional classes at Tokyo International University.

There’s one last thing I learned in all my preparation: In Japan, students in K-12 education work very hard to try to earn admission to a top college. After they graduate college, they have very early mornings, late nights, and long weeks from the day they’re hired until the day they retire. But college is the one segment in the life of a typical Japanese young adult where it is acceptable, even expected, for them to take a big step back and think about what it all means. For that reason, the college years are the most promising opportunity most Japanese people will have to receive the Gospel and take it to heart.

The Fulbright grant’s purpose is to enable me to create an intercultural learning experience. That means I am charged with explaining a lot about what makes westerners in general, and Americans in particular, tick. I get to talk about a long list of influences, including our history, our demographics, our economy, and very high on that list is the role of Christianity in our values and motivations. I get to address head-on the misunderstandings and misrepresentations of Christianity. I plan to stop far short of openly proselytizing, but the thing about evangelism is that I feel no burden to sell the Gospel; Charles Spurgeon would have described what I plan to do as letting the lion out of its cage.

For His own purposes, God stitched me together in temperament and habits to have chemistry with college students. Since 2007, I’ve been presented with five campus-wide teaching awards, and I’ve never understood quite why. All I do when I teach is turn my personality up all the way, and then explain the class content to the best of my ability, and somehow it works. But God has had a purpose for it all along. His providence brought me here in His timing, not mine, and I am more excited for what lies ahead than I’ve been about anything I’ve ever undertaken in my adult life.

If you want to keep watch over my shoulder, I’m doyleinjapan on YouTube, Instagram, and Tiktok. Please pray for me, and pray for all the students I will teach.

Written by Dr. Doyle Srader