In his aesthetic and spiritual masterpiece, Brideshead Revisited, Evelyn Waugh conjures up the Oxford of his youth in the 1920’s—an Oxford as yet unsullied, to his mind, by the encroaching efficiencies (and horrors) of modernity. For Waugh, the magic lay not in Oxford’s lecture halls or prescribed courses of study, but in the unfettered exchange of kindred minds. He writes:

I was in search of love in those days, and I went full of curiosity and the faint, unrecognized apprehension that here, at last, I should find that low door in the wall, which others, I knew, had found before me, which opened on an enclosed and enchanted garden, which was somewhere, not overlooked by any window, in the heart of that grey city.

This vision has always spoken to me. And every university, in some sense, holds out the same promise. For a short season, students on the cusp of life are yoked together with scholars from every discipline in the common pursuit of truth and beauty. Of course, the splendor is not without its attendant drudgery; but as Simone Weil wrote, perhaps the greatest benefit of hard study lies in its development of the faculty of “attention,” which is the precondition both of prayer and of true charity. And every once in a while, just off the path, one glimpses that “low door in the wall,” and through it, a glimmer of eternity. It is these less-travelled ways which, in the end, tend to lead to the defining moments of our time in college.

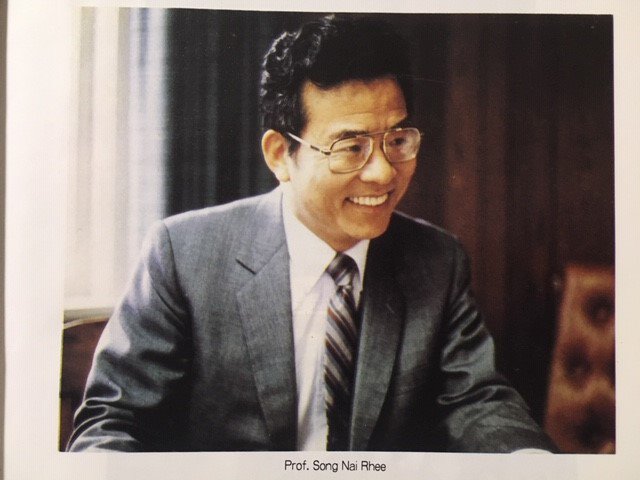

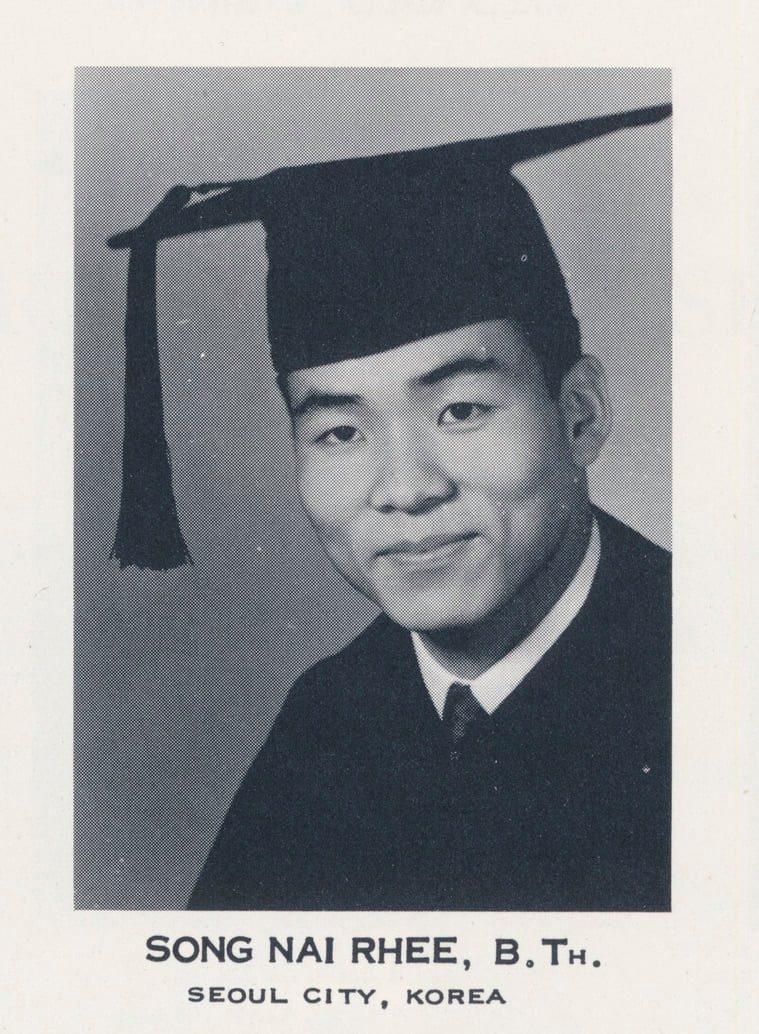

The Song Nai Rhee Honors Program at Bushnell University is one such enchanted garden. Named for legendary Professor Emeritus Dr. Song Nai Rhee ’67, the Honors Program exists as a loose “college within a college,” where students can pursue independent projects of research under the personal tutelage of individual professors. For the past two years, a select group of the most accomplished incoming freshmen has been invited directly into the program via an “Honors at Entrance” track, granting them full membership upon matriculation. Besides the deeper intellectual experience that is the heart of the Honors Program, full membership includes invitations to the Autumn and Spring Honors banquets, discussion colloquia with guest speakers, cultural field trips, informal lunch gatherings, and other exclusive events.

The Song Nai Rhee Honors Program at Bushnell University is one such enchanted garden. Named for legendary Professor Emeritus Dr. Song Nai Rhee ’67, the Honors Program exists as a loose “college within a college,” where students can pursue independent projects of research under the personal tutelage of individual professors. For the past two years, a select group of the most accomplished incoming freshmen has been invited directly into the program via an “Honors at Entrance” track, granting them full membership upon matriculation. Besides the deeper intellectual experience that is the heart of the Honors Program, full membership includes invitations to the Autumn and Spring Honors banquets, discussion colloquia with guest speakers, cultural field trips, informal lunch gatherings, and other exclusive events.

The historical interruptions of this past year inevitably caught us off guard, but they are not really so uncommon to human life, even in what we imagine to be the best of times. As C.S. Lewis put it, delivering a sermon to Oxford undergraduates in the autumn of 1939, “There is no such thing as ‘normal life.’” Even as he spoke, Nazi tanks were steamrolling Poland on their way inexorably westward.

If ever there was a life that exemplified this statement of Lewis’s, it is that of our namesake, Dr. Song Nai Rhee. I had the privilege of sitting down with him recently to hear about his boyhood in Korea and the beginnings of his passion for learning—the passion that would come to characterize his later life and reverberate through the lives of thousands of students at the University during his tenure here.

Song Nai Rhee’s early years were a veritable litany of “unprecedented times” (to use a phrase I’m sure we’re all eager to leave behind). He was just five years old at the time Lewis gave his address at St. Mary’s College and the Second World War broke out. At an age when most children are entering kindergarten, Song was forced to work to support the war effort. When the war did end, Song’s educational progress was thwarted again. With the departure of the occupying Japanese, he would now have to learn to read all over again, this time in Korean. “I still remember the morning my father made me sit down and learn the Korean alphabet,” he says. “August 1945. At the age of ten.” He adds wryly: “So even today, I still think a lot in Japanese.”

But even this relative peace would not last. Just five years later, the Korean War broke out, throwing the whole country, along with Song’s education, into chaos once more. This time the violence was right at his doorstep; guerillas from the North roamed the hills around his village, and often came down to harass the communities in the valley. “A lot of schools went up in flames,” Dr. Rhee says, “There were no classes—no schooling, period.”

It was in the midst of this impossible time that Song, only fifteen years old, took decisive action. “I realized there was no future for me in Korea,” he muses. “And by that, I mean no future for any young Korean.” And so, seeing the thousands of American troops that had arrived “to repel the North Korean invaders,” Song came to a decision born of desperation: “My future is with America.” The next step was clear. As he describes it: “‘Okay, if you want to find your future with Americans . . . study English!’ I said to myself. The problem was, the village I was living in was in the middle of Communist guerilla operations. Anyone who was associated with Americans was executed on the spot.” With the last sentence, he draws his thumb across his neck.

But despite the danger, Song went to his mother, asking her for money to buy the books he would need to teach himself English. When she told him what he already knew, that there was no money, he said, “We have rice, don’t we? Why don’t you give me just one bushel, in a bag, and I’ll take it to the city and sell it and buy the books I need.” His mother agreed, and Song took the rice and hid it on his person like a belt, for fear that he would be stopped by guerillas on his way. He undertook the journey over the mountains to the bookstore, and when he arrived, there on the top shelf were the two books he most desired: an English-Korean dictionary and an English grammar book. He spent all day sitting on the stoop of the shop, gathering the courage to speak to the manager about the books. Finally, as the storekeeper was locking up the shop, he asked Song if he was there to buy books. Song explained that he had no money, but would he accept the rice as payment? Fortunately for him, the war had made staples scarce, and so the storekeeper was all too happy to sell him the books for the bushel of rice.

Armed thus with the tools of his vision, Song set to work. His account of the ensuing weeks is remarkable. By night, he stashed the books in a hiding place cut from a corner of his home’s ceiling, to prevent their being discovered by the Communists, which would almost certainly have cost him his life. But by day, he says, “I would take them down and study all day. One sitting. I wouldn’t even get up for lunch. My mother would bring me something to eat. And one day I looked down, and my feet were swollen. Like a mountain. Because I wouldn’t stand up or move around. But you can see: I was determined.” He carried on in this way for three months. By the end of his sequestration, both books had become like “balls of cotton,” nearly disintegrated from handling. But the result? At the end of those three months, he had memorized both the grammar book and the entire English-Korean dictionary—more than two thousand English words and their definitions.

Over half a century later, in the autumn of 2020, Professor Rhee recounted some of this story at our inaugural Honors Banquet, at which he was the guest of honor. The awe of the Bushnell students, their faces lit by candlelight up and down the long table, was palpable. The sheer grit and unyielding determination that Song had shown as a young man was astounding—and hearing about his dodging murderous Communists just to be able to study English certainly put our own intellectual obstacles in perspective! As Professor Rhee said that night: “Nothing good comes easy. If it’s easy, it’s nothing.”

Over half a century later, in the autumn of 2020, Professor Rhee recounted some of this story at our inaugural Honors Banquet, at which he was the guest of honor. The awe of the Bushnell students, their faces lit by candlelight up and down the long table, was palpable. The sheer grit and unyielding determination that Song had shown as a young man was astounding—and hearing about his dodging murderous Communists just to be able to study English certainly put our own intellectual obstacles in perspective! As Professor Rhee said that night: “Nothing good comes easy. If it’s easy, it’s nothing.”

And so ended the first chapter in Song’s journey—a journey that would lead him unexpectedly to a Christian missionary high school in Korea (he had come from a strict Confucian family), and then eventually to a little school called Northwest Christian College, halfway around the world in Eugene, Oregon, to which he would eventually return and teach for decades. These further chapters are for another time. But in these early days of the Song Nai Rhee Honors Program at Bushnell University, may his story be a guide and a bracing draught of courage on those long and wearisome nights of study. And in the coming years, may Honors at Bushnell truly become a low door in the wall of our beloved college for those who seek one, leading to an enchanted garden—where the Son of Man walks in the cool of the day hand in hand with those of us for whom, in light of our calling, the pursuit of truth and beauty is not only a duty but a sacred and sanctifying joy.

Dr. James Watson, Associate Professor, English, was born in Austin, Texas, and grew up, for the most part, in Beaverton, Oregon. His undergraduate education in applied linguistics, philosophy, and ancient languages was undertaken at Wheaton College and Portland State University. During a hiatus from academia, James worked as a consultant to an accounting and business management software firm. He later went on to complete his doctorate in English Literature at Baylor University. In addition to teaching literature at Bushnell, James serves as the Director of the Song Nai Rhee Honors Program. He believes one of the highlights of teaching at Bushnell is “the variety and depth of intellectual and faith backgrounds represented by the student body.” In his scholarly and writing life, Dr. Watson has published articles on Cormac McCarthy, Jaques Derrida, Ernest Hemingway, and more. He published his first novel, A Window on the Door, several years ago and has also written numerous scripts for short films and documentaries. He is now working on several projects aimed at film and television markets.

When he is not on campus or working at home in his writing shed, Watson says he loves spending time with his wife of 17 years, Meghan, and their five sons, and that he has “acquired an outsized affection for well-tended gardens and antique motorbikes.

–Dr. James Watson